Download this Brief as a PDF: ![]()

English | Français | Português | العربية

Adapting Sahelian force structures to lighter, more mobile, and integrated units will better support the population-centric COIN practices needed to reverse the escalating trajectory of violent extremist attacks.

Niger’s armed forces patrol in the northern region of Agadez. (Photo: Souleymane Ag Anara/AFP)

Highlights

- Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger have experienced a near uninterrupted expansion in militant Islamist violence over the past decade, underscoring the need for an alternative security strategy. Central to this is the recognition that these violent extremist groups employ irregular tactics and operate as local insurgencies, requiring a sustained counterinsurgency campaign.

- Elevating the effectiveness of Sahelian forces will require a more integrated, mobile, and population-centric force structure bolstered by enhanced logistical and air support capabilities.

- Building positive relations with local populations is not just a question of morality or legitimacy but also an essential means of weakening support to insurgents.

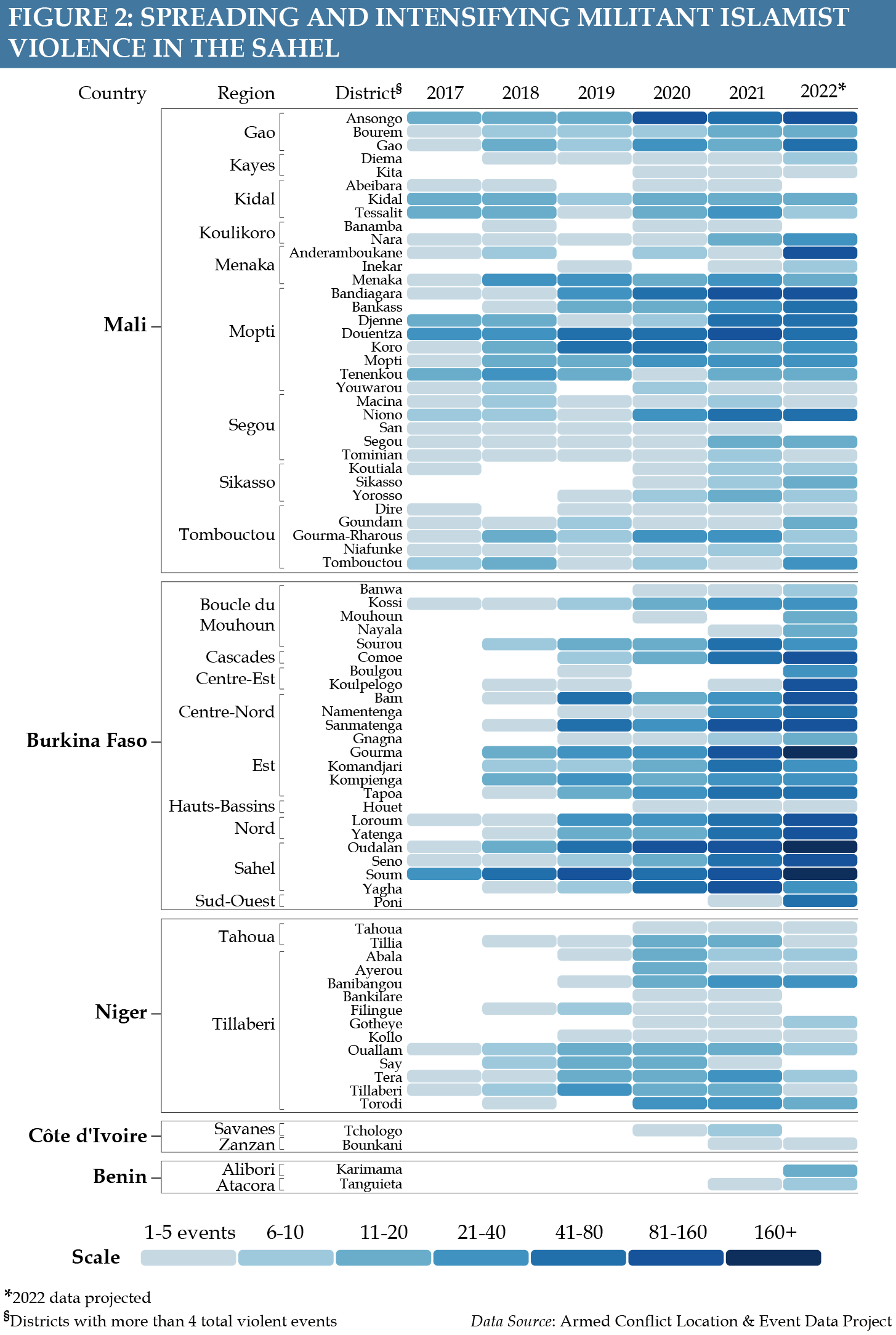

Militant Islamist violence in the Sahel is accelerating faster than in any other region in Africa. After nearly a decade of conflict, violent events in the Sahel (specifically Burkina Faso, Mali, and western Niger) are surging—with a 140-percent increase since 2020 and no signs of abatement. Militant Islamist group violence against civilians in the Sahel represents 60 percent of all such violence in Africa and is projected to increase by more than 40 percent in 2022.1 This uninterrupted escalation of violence has displaced more than 2.5 million people and is on pace to kill more than 8,000 individuals in 2022 (see Figure 1).

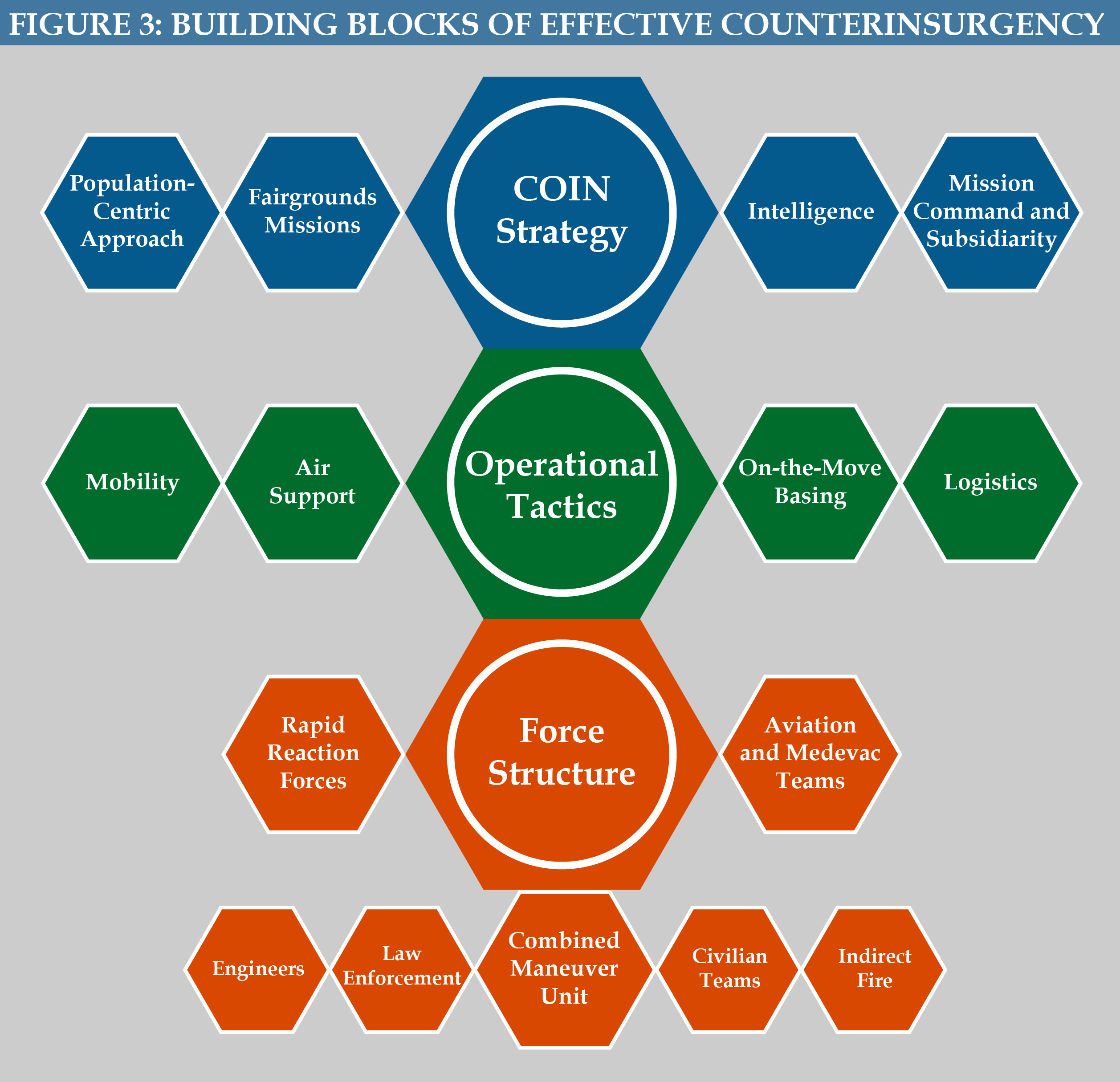

Government control over the vast rugged territory has diminished over the years, revealing an inability to sustain pressure on militant Islamist groups and to provide security for communities. Sahelian security forces have suffered heavy losses in the conflict. Militants have successfully targeted security and defense forces in their attacks throughout Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. Superior mobility and intelligence capabilities have allowed the militant groups to overrun static military bases, resulting in hundreds of casualties among armed forces. Military coups in Mali and Burkina Faso, moreover, have diverted precious attention and resources from the fight, allowing militants to gain momentum and expand. In 2021, a record 73 administrative districts witnessed violent events associated with militant Islamist groups, up from 35 districts in 2017 (see Figure 2).

Government control over the vast rugged territory has diminished over the years, revealing an inability to sustain pressure on militant Islamist groups and to provide security for communities. Sahelian security forces have suffered heavy losses in the conflict. Militants have successfully targeted security and defense forces in their attacks throughout Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. Superior mobility and intelligence capabilities have allowed the militant groups to overrun static military bases, resulting in hundreds of casualties among armed forces. Military coups in Mali and Burkina Faso, moreover, have diverted precious attention and resources from the fight, allowing militants to gain momentum and expand. In 2021, a record 73 administrative districts witnessed violent events associated with militant Islamist groups, up from 35 districts in 2017 (see Figure 2).

The conflicts in the Sahel are complex and cannot be reduced to any single factor. The deteriorating security environment, nevertheless, highlights the need to reexamine and recalibrate the strategy Sahelian countries employ for their security forces to confront this growing threat. At its core, this requires recognizing that Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger face local insurgencies (rather than isolated terrorist threats). Consequently, reshaping security forces specifically for counterinsurgency is paramount to stabilizing the Sahel. This implies several important changes with respect to military capabilities, doctrine, and force structure as well as the place of armies in the larger context of justice and law enforcement.

Click here for a printable PDF.

Developing a Counterinsurgency Strategic Orientation

A first step in assessing a security strategy is understanding the threat. Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger are threatened by disparate violent extremist groups mobilized by distinctive geographic, ethnic, ideological, and political motivations.2 Although these groups are often characterized as belonging to one of two overarching banners—the Al Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nasrat al Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS)—the Sahelian militants are less extensions of global terrorist organizations than expressions of local conflicts. These militant groups are led by charismatic and politically minded local spoilers who channel and exploit local grievances related to perceived injustice, political marginalization, ethnic discrimination, and poverty. Some people are receptive to jihadist narratives because of genuine weaknesses of Sahelian governments, which have been characterized as neglectful at best, abusive at worse. Sahelians often perceive their countries’ limited justice systems as slow and venal. And there is a perception of broad impunity with respect to abuses, injustice, and corruption.

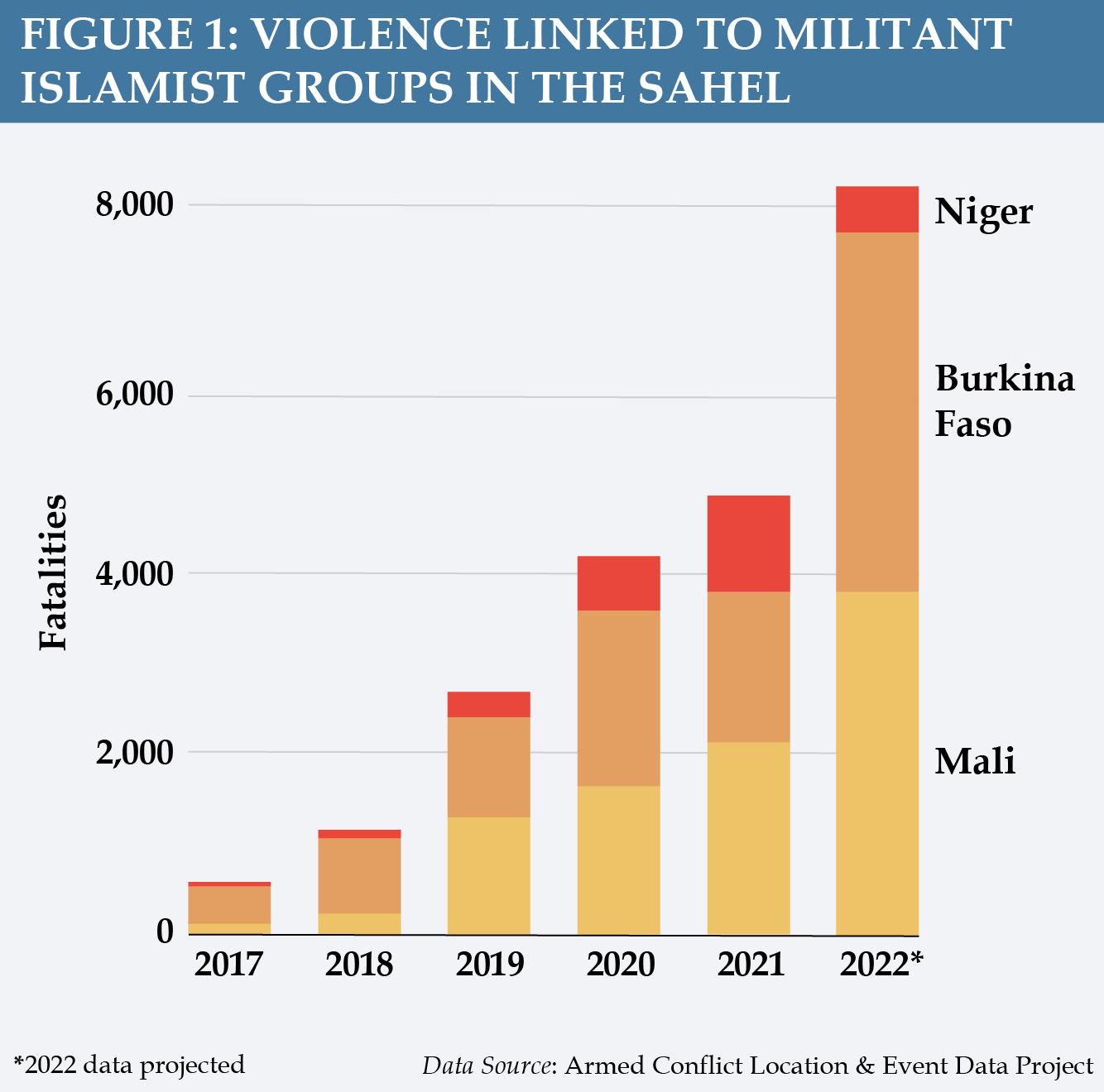

Given the local, societally based nature of the security threat in the Sahel, shifting the strategic orientation guiding Sahelian armed forces to counterinsurgency (COIN) is warranted. This requires a “population-centric” approach, which means limiting as much as possible the application of violence. It also entails complementing military action with initiatives to improve living conditions as well as the provision of justice and law enforcement. In short, successful COIN demands a different kind of military and governance strategy.

These basic premises of COIN require capabilities that enable militaries to interact with local communities and build positive relationships. These relationships are essential, as are the respect for the law of war and rule of law. It might be an exaggeration to say it is more important that soldiers learn to be model citizens than be proficient at combat tactics, but only just. Effective African security forces must enjoy the acceptance and trust of the people they protect and serve.3

“Sahelian armies must be ‘republican’ in the sense of representing the values of the nation they defend.”

This means that Sahelian armies must be “republican” in the sense of representing the values of the nation they defend.4 The imperative for good relations with the population also has concrete implications for recruitment and fostering a diverse force that reflects society. Diversity presents challenges related to cohesion. However, fostering cohesion and an esprit de corps among diverse formations can enhance the military’s capabilities while also reinforcing its republican qualities.5

Military justice is also a key component. The gendarmeries nationales that are common in Francophone Africa play a central role by straddling the military and law enforcement. Gendarmeries typically police civilian populations and have a provost function, meaning they monitor the armed forces. The gendarmeries and police should be equipped with the necessary staff and resources to address complaints of human rights violations. At the very least, this should help reduce instances of security forces abusing civilians, which are not only counterproductive but also a boon for insurgents’ recruitment. Upholding human rights also strengthens government legitimacy. Specified troops might be designated “human rights referents” for an operation, which would make them responsible for ensuring that the provisions of armed conflict and international humanitarian law are observed.6

Mauritanian Civil Military Cooperation Teams distributing supplies to a local school during Flintlock near Kaedi, Mauritania. (Source: U.S. AFRICOM/Spc. Brunschmid)

Integrating civilian teams at the battalion level to identify problems related to governance as well as opportunities for mobilizing the population’s support can, similarly, improve COIN efforts.7 These teams help ensure that the government acts on matters related to policing, infrastructure, health care, education, agriculture, and veterinary services, effectively responding to the interests and needs of local populations.

These teams are often the first to arrive with the capacity to respond to civilians’ needs and operate as a vanguard of government services. In doing so, they lay a foundation for a new social contract that can tilt the balance of trust back toward the government in counterinsurgency conflicts. General Oumarou Namata Gazama, the Nigérien commander of the G5 Sahel Joint Force in 2019-2021, coined the term “missions foraines” (fairgrounds missions) in reference to efforts toward this goal. The idea was for civil administrators, medical teams, and development experts to accompany military operations to re-implant an embryo of the state in areas where it had not been operational.

Basic Imperatives for a COIN Army in the Sahel

Beyond the strategic orientation of Sahelian armies, there is a need to build the region’s armed forces in accordance with the Sahel’s security context. Scarce resources and vast spaces mean there will never be enough troops. Instead, the armed forces would benefit from adaptive light maneuver units with commensurate air and indirect fire support, intelligence capabilities, logistics units, maintenance capabilities, and an operations footprint that avoids static positions whenever possible.

Mission Command. A successful COIN campaign within the Sahelian context requires a high degree of what Americans refer to as “mission command” and the French idea of “subsidiarity,” which together translate into building small and modular combined arms maneuver units that exercise a high degree of autonomy.8 It means forming company-sized (60-200 troops) or even half-company-sized mobile maneuver units that pull together different elements to include intelligence, engineering, and civil-military affairs, as required. Integrating units in this manner allows for a wide range of capabilities within a small force to enable greater autonomy to complete the mission.

Mission command goes beyond unit formation, however. It requires high quality officers and noncommissioned officers who have the ability and the authority to act as they think best to fulfill their commanders’ intent during unified land operations.9 Recruitment, human resource management, and, of course, training are key ingredients. So far, attempts to develop such combined arms maneuver units, like Mali’s combined arms tactical groups (GTIAs), have failed, in part, due to a poor administrative foundation and lack of human capital.10 Additionally, fostering unit cohesion in what can amount to a patchwork of personnel drawn from existing units has presented significant, if predictable, challenges.

“The deficiencies in Sahelian intelligence services have less to do with equipment than with skills and politics.”

Mobility. The harsh, expansive terrain dictates that Sahelian militaries need to eschew heavy vehicles for lighter ones and, whenever possible, operate as airmobile or even airborne forces. Weapon-mounted pick-up trucks (known as technicals), motorcycles, and other light tactical vehicles make a great deal of sense. Mali’s motorcycle- equipped light reconnaissance and intervention units (ULRI) serve as a classic mounted-infantry and light cavalry. Platoons from these company-sized units can cover as much ground as possible, quickly, while avoiding roads that might host IEDs.

Mobility generally comes at the expense of protection and firepower. Forces need the dexterity to operate like insurgents with respect to mobility, but they must be better. Specifically, Sahelian militaries must be good enough to be able to defeat their adversaries most of the time.11 A few armored vehicles with .50 caliber machine guns may suffice, assuming the vehicles are well suited for the climate and terrain. An armored vehicle like the French VAB (Véhicule de l’avant blindé) or a mine-resistant, ambush-protected vehicle (MRAP) armed with the same weapon, might have made a critical difference in 2017 when Nigerien forces, accompanied by a team of U.S. special forces, were ambushed on patrol near the town of Tongo Tongo.

Nigerien Armed Forces conduct a convoy movement during Flintlock exercises. (Source: U.S. Army/Staff Sgt. Runser)

Two basic types of mobile units offer strong potential: a mobile strike force, comprised of technicals, and an airborne or airmobile rapid reaction force. The former would, at least, also have some artillery capabilities. Sahelian militaries today have mortars and other low-cost, lightweight direct and indirect fire platforms, but they do not have them in sufficient quantities. Furthermore, truly integrating these platforms in combined-arms fashion is a challenge for all armies, requiring hours of training and preparation and thus resources. Sahelian armies also have towed artillery, but their utility considering the logistical requirements is questionable.

Air Support. Ideally, Sahelian troops could call upon close air support. In this regard, French tactics in Chad in 1969-1972 are instructive. France fielded a force of light infantry that, at its height, consisted of five companies and a company of machine-gun cars. They made up for their scant numbers with high mobility (facilitated by light logistical requirements), a small fleet of transport aircraft, and a squadron of six to nine AD-4 Skyraider ground attack planes. In effect, the French counted on their soldiers being skilled enough to survive contact with enemy forces long enough for the Skyraiders to arrive and provide decisive firepower.

Today’s Super Tucano turbo-prop attack aircraft along with the growing number of attack, reconnaissance, and transport planes and helicopters in Sahelian fleets (Mi-17s, Mi-24s, Tétras, etc.) are more than up to the critical tasks of transportation, reconnaissance, and fire support. Mali has Super Tucanos and attack helicopters. The helicopters have been effective; we have no information about the Tucanos. Transport aircraft, whether fixed-wing or rotary-wing, also vastly improve medevac capabilities, which go a long way toward bolstering a force’s morale. Crucial to building this inventory, however, is the development of maintenance platforms to ensure the equipment does not fall into disrepair scuttling the air support fleet.

Intelligence. Intelligence is absolutely crucial in a civil conflict, all the more so when government security services are undersized and weak. Without good intelligence they are likely to strike out blindly and cause far more harm than good. They need to know whom to target and where, where to go, and how to discern between militants and innocents. The deficiencies in Sahelian intelligence services have less to do with equipment than with skills and politics. Intelligence sharing between agencies is a key challenge, for example.

Logistics and Maintenance. A difficult but no less critical capability is logistical support, which tends to be neglected. Logistics is a challenge for any army, especially an under-resourced one. However, expeditionary logistics of the kind required for the sort of Sahelian force envisioned here is as difficult as it is necessary.

The goal of logistics should be to maximize the autonomy of maneuver units.12 This requires having the means to deliver required supplies to the right place at the right time. Given limited capacity, however, most systems will and do struggle. Malian forces are often stuck in their bases for lack of operational vehicles. After a disastrous attack on a Burkinabè gendarmerie base in November 2021, it was revealed that the garrison was weak from hunger. Even the French Army, which excels at such operations, nearly came to grief during Operation Serval in 2013 as it struggled to make sure its swiftly advancing troops had enough water to stay alive in northern Mali. There are two key logistical lessons for Sahelian armies: the first is to invest as much as possible in developing their logistical capabilities, and the second is to do everything possible to reduce their logistical requirements.

“There are two key logistical lessons for Sahelian armies: the first is to invest as much as possible

in developing their logistical capabilities, and the second is to do everything possible to reduce their logistical requirements.”

Malian ULRIs significantly improved their mobility with inexpensive Chinese motorcycles, for example. Crucially, these motorcycles were easy for Malian troops to maintain and repair because they could buy parts on the local market, reducing their reliance on faulty supply chains. In contrast, other Malian soldiers have often been immobilized because they could not keep their vehicles in working order due, in part, to the weakness of their logistical chain. The ULRIs reportedly also benefited from being issued pick-up trucks and radios that were commonly available in the Sahel.

Sahelian armies, relatedly, often have incompatible equipment inventories, which reflects the diversity of their donors but also the absence of clearly articulated requirements. Sahelian militaries might not feel they are able to refuse gifts, or perhaps they lack a policy of identifying what may or may not be useful. The resulting diversity of equipment is a liability for forces with poor logistical capabilities.

On-the-Move Posture. Well-placed and well-defended bases are crucial for being able to stage operations and project force into remote areas. One thorny problem is finding an appropriate balance between dispersion and concentration. Static defenses and permanent bases should be avoided. They become easy targets and make it more difficult for forces to take the initiative. Fixed positions also present liabilities given that they more easily fall under enemy observation. Routes become predictable. Operations become transparent. Thus, even advanced bases, which offer a compromise between mobility, protection, and control of the surrounding area, must be temporary. They should have a life span of 10-30 days.13 In contrast, Sahelian forces appear to tend toward static positions that limit interactions with local populations and their ability to collect intelligence. Malian troops, especially in northern Mali, tend to hunker down in large bases for self-protection and because vehicles fall into disrepair.

Insurgents also find it relatively easy to shut down government forces’ mobility by mining the roads they routinely take to move from one base to another or to leave bases to conduct operations. Blind and isolated, Sahelian soldiers have suffered grievous losses after their bases have been overrun. An on-the-move posture also requires engineers and engineering skills. Berms, ditches, fencing, and other simple basing features can improve protection with little associated cost apart from manpower and know-how. These defensive tactics can also be adapted for mobile units.

African Models

Two African counterinsurgency models offer relevant insights for the Sahel—Mauritania’s Special Intervention Groups (GSIs) and Cameroon’s Rapid Intervention Brigade (BIR). Both have been praised for their efficacy against bandits and militant groups, although human rights violations have sullied the Cameroonian units’ reputation. Both coordinate their movements with aviation assets that serve as transportation and reconnaissance platforms as well as provide fire support.

The BIR demonstrates a “tactical and operative flexibility” similar to Rhodesian, South African, and Israeli operations in the 1970s and 1980s.14 The BIR consists of roughly 5,000 men divided into 5 battalions. These include airborne, amphibious, armored reconnaissance, and intelligence units, as well as an airborne cavalry unit known as an airmobile rapid intervention group. The BIR’s basic tactical element is the company-sized light intervention unit (UIL) to which armor, artillery (mortars), and intelligence elements are attached.

“This has revealed the uselessness of having a few high-speed companies while the rest of the force is unpaid, lacks magazines for their guns, and has inoperable vehicles.”

UIL commanders can call on enough artillery support to break even a numerically superior adversary. Critically, the Cameroonian combined arms combat groups benefit from a decentralized command structure (akin to mission command), which reportedly enhances their agility and adaptability during operations. Moreover, Cameroon is recognized for effectively exploiting its airmobile capabilities, thereby multiplying the advantages of its combined arms.15

Cameroon’s armed forces have Alpha Jets, as well as three squadrons of attack and transport helicopters, Mi-24s among them, and various patrol/reconnaissance aircraft offering significant air support. The Mi-24s are reportedly attached to the BIR. Cameroon, moreover, has in its inventory modern armored vehicles, including French Bastion MRAPs and Israeli GAIA Thunders, both of which represent an appropriate mix of mobility, protection, and firepower.

Battalion-sized battlegroups (about 1,000 troops) of the sort Cameroon exhibits with its BIR provide one possible blueprint. However, this model may require resources not available to the militaries of the Sahel. This format pulls the constituent parts from standing infantry, armor, and various combat-support and combat-service-support regiments on an as-needed basis. This translates into a degree of modularity that Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger may struggle to replicate and sustain.

Sahelian armies ought to eschew this modularity in exchange for standing combined arms units with organic capabilities similar to the Mauritanian GSI. These eight small-unit teams are versatile in both thinking and execution. The combat teams have been well equipped with light vehicles and supplies, especially fuel, water, and ammunition, for sustained independent operations lasting several days in the remote desert. To strengthen group cohesion and motivation, each unit is comprised of about 200 men who have served together for several years. Importantly, they have the mobility, combat support, and combat service support they require to execute their mission.

Enhanced air support has been essential to these ground operations even while coordination remains basic. Mauritanian airmen do not have the advanced capacities of their North African counterparts, but a few assets—Cessna surveillance planes, Super Tucanos, and Chinese helicopters—have proven sufficient to detect suspicious activity and guide the GSI on the ground. Integrated intelligence has also played a critical role in GSI counterterrorism operations. The rise of militant Islamist activities in the Sahel spurred efforts to develop both field-level human intelligence networks and technical capabilities. These range from the revitalization of existing competencies and assets tailored to operate in remote desert areas to the acquisition of modern surveillance radars.16 Many of these innovations serve as instructive examples for other Sahelian countries.

International Support and Security Cooperation

International security partners have long suffered from ambivalence regarding how best to support Sahelian countries without being drawn into their internal political struggles. In simple terms, they have been willing to help Sahelian governments combat “terrorists” but not armed rebels. The distinction is dubious, but the ramifications have been real: a pattern of trying to provide discrete capabilities to limited numbers of soldiers rather than attempting to improve the capabilities of the overall force.

This has revealed the uselessness of having a few high-speed companies while the rest of the force is unpaid, lacks magazines for their guns, and has inoperable vehicles. Even EUTM, the European Union’s training mission in support of Mali’s army, refrained from equipping the units with which it worked. Consequently, the Sahel’s best forces are hobbled by problems as basic as the lack of rifle slings, let alone enough mortar rounds for training.

EUCAP training in Niger. (Source: Ministerie Defensie / Gerben Van Es)

Absent a clear consensus on a basic blueprint for Sahelian forces, international security partners have tended to offer “ready-to-wear” solutions that have little relevance. Security assistance partners would do well to think in terms of COIN and help Sahelian armies develop the appropriate capabilities.

Another issue is that the counterterrorism focus, encouraged by the reluctance to deal with Sahelian domestic problems, amounts to a concentration on combat operations often to the neglect of the noncombat side of a population-centric approach. It is for this reason that the paradigm switch to counterinsurgency is important. COIN is not just about combat skills but also the restoration of community trust in government.

In some cases, this poses a problem for donor countries because of bureaucratic divisions over who can work with armies and who can work with law enforcement agencies. COIN armies require the integration of law enforcement and the military justice system. International partners also need to think in terms of improving the efficacy of integrated formations, like the GTIA, and the ability of subgroups within these formations to work autonomously.

The armies of the Sahel have come a long way since their Cold War days. One still finds old T-55s and BTRs alongside 1980s-vintage artillery (if not older), much of which is derelict and litters parking lots. However, one finds plenty of more suitable, and operable, light vehicles and appropriate aircraft, as well as MRAPs. Therefore, it is not a question of radically transforming equipment inventories but rather completing the forces’ evolution to embrace COIN doctrine.

“COIN is not just about combat skills but also the restoration of community trust in government.”

On paper, for example, Mali’s army has many of the correct pieces in place—most notably the eight GTIAs, which suggests a degree of mobility and modularity. In practice, however, they lack the cohesion and skills to function as they should. This is, in part, an administrative failing. Poor management of human resources means no one is tracking which soldiers have been trained and by whom, and soldiers assigned to GTIAs rotate out of them. Whatever skills Malians acquire, consequently, tend to dissipate.17 This goes a long way toward explaining why Mali’s army and GTIAs made only modest progress during the 9 years the European training mission supported them. Even if the GTIAs function well, they lack the specific capabilities required for COIN, especially regarding military justice and civil-military relations. Until these issues are addressed, international assistance spent on other priorities is not likely to amount to much.

Building a More Effective Sahelian Army

Sahelian governments need a clear strategy and doctrine for their force structures to effectively address their security threats. A useful first step would be to embrace the paradigm of counterinsurgency. This translates into a strategy that pairs combat operations with a population-centric approach that is intended to strengthen relations with local populations and recast the social contract. It requires a force that has built-in elements to work with local communities, to provide justice and law enforcement for them, and to police the military. Absent this, an approach focused purely on combat operations is destined to fail. Sahelian forces simply cannot kill enough insurgents to prevail, and their attempts to do so have been counterproductive. A COIN force should offer, at the very least, the advantage of not preying upon civilians and, at most, sustained pressure on insurgent groups coupled with protection for communities. The following offer a set of recommendations and policy priorities that contribute to these goals.

“A strategy that pairs combat operations with a population-centric approach … strengthens relations with local populations.”

Build a ground force around battalion-scale, mobile, combined arms task forces consistent with a COIN population-centric strategy. The force requires the integration of police, gendarmes, and civilian elements focused on the provision of essential government services. The importance of this cannot be overstated. These elements complete a population-centric strategy that restores relations with local communities and uses organic intelligence capabilities to degrade insurgent threats.

Alongside intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities, combined arms task forces need to cultivate a command culture built around the practice of mission command to help Sahelian militaries get the most out of small forces in their resource-constrained environments. Toward this end, Sahelian forces will need to identify practical and pragmatic steps to build out their combined forces. These include:

➢Integrating indirect-fires for true combined arms operations in battles, with mortars being a suitable low-cost and relatively mobile option.

➢Developing a stronger engineering capability, at least for the sake of improving static defenses.

➢Creating an aviation arm that can provide necessary fires but also conduct rapid airmobile operations with possible standalone, quick response, and reinforcement options.

While fully transforming a force is a years-long process, requiring multiple iterations with persistent support and adaptation to be achieved, even initial steps taken in this direction should yield improvements.

Take community relations and engagement seriously. Far more important than considerations of force structure and mobility is the imperative to build positive relations with local populations. It is not just a question of morality and legitimacy (both valuable commodities in a counterinsurgency) but also of avoiding counterproductive actions such as killing civilians, which tends to strengthen the insurgents’ cause. The unwillingness or inability of Sahelian governments to provide these protections, consequently, should shape other forms of international partner engagements.

Strengthen intelligence capabilities. Improving the collection and analysis of intelligence requires greater investments in technical collection capabilities, to include ground sensors, drones, and the ability to intercept phone and radio communications. More importantly, collectors and analysts at all levels need training. In addition, Sahelian countries must develop institutional mechanisms for sharing information, both at the tactical level and higher up. This requires high-level political support for inducing different services to cooperate and coordinate. An entity close to the head of state should be empowered to play a role analogous to the American Office of the Director of National Intelligence or the National Security Council, which has supervision over intelligence and can provide top-level direction for all intelligence entities. This must be accompanied by robust oversight protections against the abuse of intelligence capabilities for political ends.

Invest in and support logistics capacity to sustain COIN posture. Sahelian forces need to strive for as much homogeneity as possible with respect to vehicles and weapons systems to ease logistical burdens. Security assistance should provide copious stores of commonly available parts and work to help Sahelian armies develop their logistics and sustainment capabilities. Ideally, Western partners might consider larger scale packages (e.g., thousands of assault rifles of the same model with associated magazines and slings; hundreds of mortars of different calibers, with ample ammunition).

Support battalions with a rapid reaction force capable of a wide range of operations. Sahelian armies need a rapid reaction force, ideally airmobile, but otherwise operating using technicals and possibly a few MRAPs. This presupposes the existence of a tactical air support group, which uses fixed- and rotary-winged aircraft to provide a variety of missions from medevac to air assaults and fire support. Mali and Niger also require riverine capabilities, perhaps to be provided by a separate group that is not organic to the battlegroups, but which can team with any of them, as appropriate.

“Building positive relations with local populations is not just a question of morality or legitimacy but also an essential means of weakening support to insurgents.”

International partners should work with their host-nation partners to develop coherent blueprints from parts to education. Sahelian strategy should inform their international partnerships, guiding what international partners teach and the equipment they provide. Like-minded security partners might consider joint international ventures to provide larger interoperable equipment packages to minimize waste and avoid logistical pitfalls. International partners should also refrain from donating equipment if not of a type that is already in military inventories.

Beyond equipment, international security assistance programs can also work to ensure Sahelian partners leverage combined arms capabilities to operate at scales both smaller and larger than the battalion-scale battle groups. Assistance providers need to think in terms of improving the efficacy of the integrated formations for the Sahelian context. Given the vast terrain and limited resources, the ability of subgroups to work autonomously will be essential. This requires greater attention to long-term professional military education across units and their leaders. A more comprehensive approach to training that encompasses the entire life cycle of the Sahelian soldier is needed.

Dr. Michael Shurkin is Director of Global Programs at 14 North Strategies and the founder of Shurbros Global Strategies. He served as a political analyst in the CIA and was a senior political scientist at the RAND Corporation. He thanks Captain Joseph Michael McGiffin, U.S. Army, for his assistance with this project.

Notes

- ⇑ Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Surge in Militant Islamist Violence in the Sahel Dominates Africa’s Fight against Extremists,” Infographic, January 2022.

- ⇑ Daniel Eizenga and Wendy Williams, “The Puzzle of JNIM and Militant Islamist Groups in the Sahel,” Africa Security Brief No. 38, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, December 2020.

- ⇑ Helmoed Heitman, “Optimizing Africa’s Force Structures,” Africa Security Brief No. 13, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 2011.

- ⇑ Michael Shurkin, John Gordon IV, Bryan Frederick, and Christopher G. Pernin, “Building Armies, Building Nations: Toward a New Approach to Security Force Assistance,” RAND Corporation, 2017a; Michael Shurkin, Stephanie Pezard, and S. Rebecca Zimmerman, “Mali’s Next Battle: Improving Counterterrorism Capabilities,” RAND Corporation, 2017b.

- ⇑ Shurkin 2017a.

- ⇑ Pauline Le Roux, “Responding to the Rise in Violent Extremism in the Sahel,” Africa Security Brief No. 36, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, December 2019.

- ⇑ Eeben Barlow, Composite Warfare: The Conduct of Successful Ground Force Operations in Africa (Pinetown, South Africa: 30° South, 2016).

- ⇑ Armée de Terre, Doctrine d’emploi des forces terrestres en zones désertique et semi-désertique, Edition-Provisoire, EP 20.440 (Paris: Centre de Doctrine d’Emploi des Forces, 2013); Barlow, Composite Warfare; Laurent Touchard and Michel Goya, Une révolution militaire africaine: Lutter contre les organisations armées en Afrique subsaharienne, 2018.

- ⇑ Michael Shurkin, “France’s War in Mali: Lessons for an Expeditionary Army,” RAND Corporation, 2014.

- ⇑ Denis M. Tull, “The European Union Training Mission and the Struggle for a New Model Army in Mali,” Research Paper No. 89, Institut de recherche stratégique de l’école militaire, Paris, 2020.

- ⇑ Touchard and Goya.

- ⇑ Armée de Terre, 9.

- ⇑ Armée de Terre, 34.

- ⇑ Laurent Touchard, Forces armées africaines: organisation, équipements, état des lieux et capacités (Paris: Éditions LT, 2017), 338.

- ⇑ Touchard, 339.

- ⇑ Anouar Boukhars, “Keeping Terrorism at Bay in Mauritania,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, June 16, 2020.

- ⇑ Dan Hampton, “Creating Sustainable Peacekeeping Capability in Africa,” Africa Security Brief No. 27, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, April 2014.